Buyeo (부여)

The modern city of Buyeo maintains what remains of the once great Baekje capital city of Sabi (538-660 A.D.). The last of three successive capitals, Sabi (Buyeo’s name at the time) was where the king and his court resided when disaster struck in 660 A.D. when the kingdom was seized by a Silla-Tang Alliance. Many original historical sites remain in their ruined—yet hauntingly beautiful—state, to include the once formidable Busosanseong and portions of the old city wall. Other sites, like the palace and associated temple complex, have been rebuilt nearby with careful attention paid to ancient plans. As well you can find a wonderful museum dedicated to the Kingdom of Baekje.

My first visit to Sabi—at least in my mind’s eye that’s where I went—took place in 2019, just before the pandemic made travel impractical if not downright impossible. Our trip was short by necessity, and it rained the whole day, making it difficult to get around or even take decent pictures.

Our second visit was more substantial . . . and STILL didn’t make it everywhere I wanted to see! That said, we did finally make it up and around historical Busosanseong, visited the royal tombs, walked a stretch of the old Sabi City wall, visited a royal Baekje garden at Gungnamji, and walked the grounds of one of Korea’s oldest Buddhist Temple complexes at Jeongnimsaji. All in all, a full day, taking into account the drive down and back, and yet still more to see there. Certainly . . . one more trip should do it!

Buyeo Cultural Center

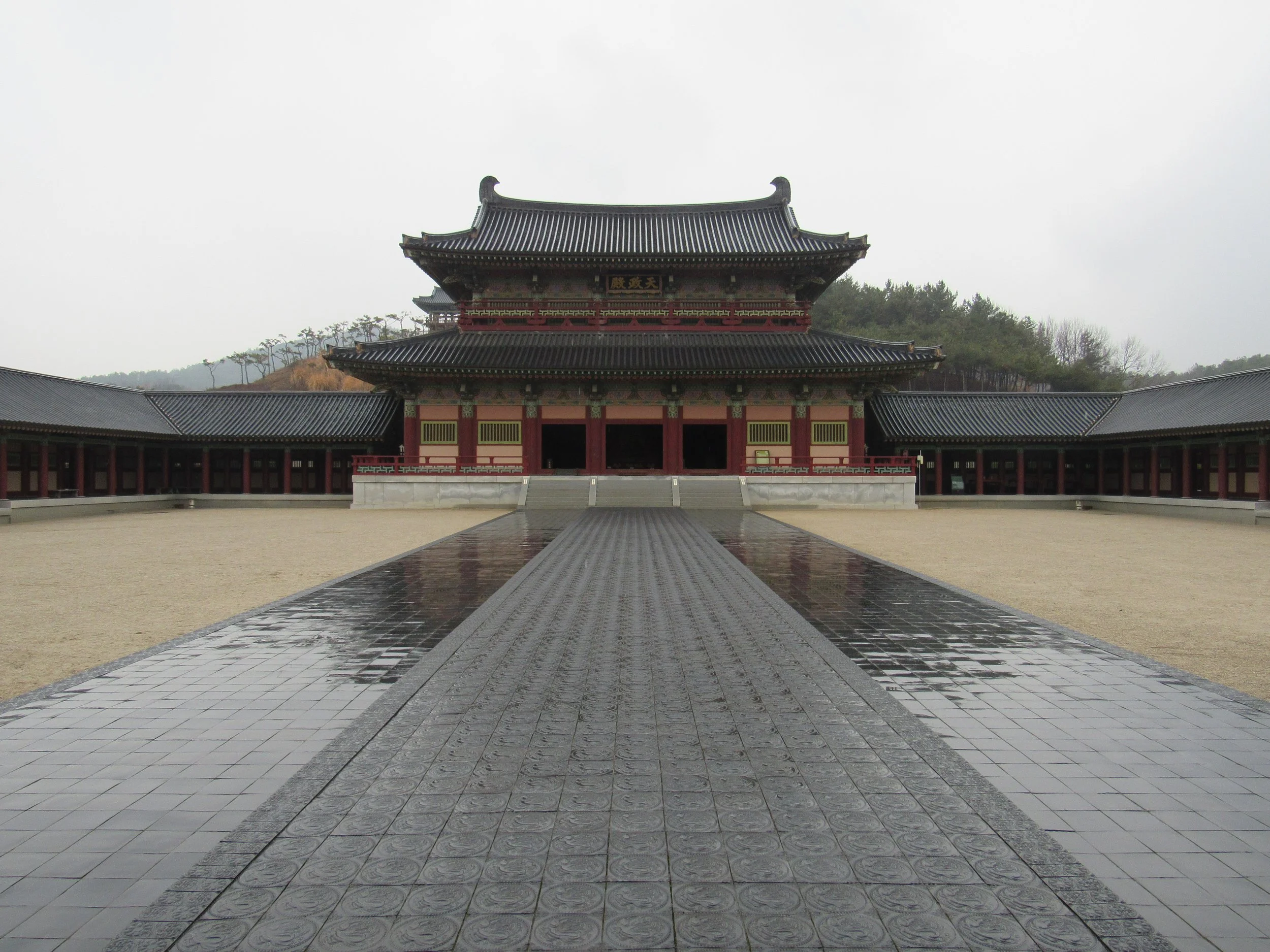

The reconstructed Baekje Royal Palace—called Sabigung—is well done, and gives a pretty good idea of the scale and, frankly, wealth amassed by the kingdom prior to its fall. This view faces the main gate to the palace compound beyond, with a pavilion on the rise behind it.

The reconstructed temple complex, complete with five-story pagoda. Exquisitely done, this entire complex again provides the feel for life in the Baekje capital and royal precincts.

The main courtyard of Sabigung, highlights the paved and raised central way leading to the King’s hall.

Within that hall, the King of Baekje’s throne set up on the royal dais, backed by the symbol of Baekje.

Administrative buildings within the palace. This is where the generals and bureaucrats did their thing to keep the kingdom running and, preferably, safe from harm.

Within the museum itself, this wonderful terrain model of the city of Sabi as it might have appeared just prior to its fall. Taken from the north, the fortress of Busosanseong lies just south of the River with the city of Sabi sprawling to the south and east beyond. The long walls of Sabi were a wonder at the time both for their length and the cost it took to face them with cut stone. However, that long defensive line—and the need to man it—turned into a liability after the kingdom’s best troops were lost in a failed attempt to defeat the Silla-Tang alliance piecemeal, leaving the city without its stoutest and most effective defenders.

Life-size dioramas depicting everyday life in Baekje fill the museum, making it both unique, and well worth the trip!

Behind the museum you find the reconstructed palace and temple…but behind the palace, there are a couple more historical sites worth at least strolling through. The first is a good representation of a Baekje-era village, highlighting both ends of the economic spectrum. As well, and not depicted here due to on-going renovations and a sudden, heavy downpour during our visit, is a much older exhibit depicting what appeared to be a Korean Bronze age fortified village. One of the reasons I’m dying to get back there!

Busosanseong

The defensive citadel of the Kingdom of Baekje’s final capital at Sabi. Busosanseong also served to anchor Nanseong, the city walls of the capital. There’s a lot to see on the network of wooded mountain trails, leading to the dramatic Nakhwa-am. It was there that the ladies of the Baekje royal court reportedly jumped from the high cliff to their deaths in the Geum River rather than be captured by the Tang and Silla invaders.

The last remaining (reconstructed) gate complex at Busosanseong, looking largely as it would have 1400 years ago.

An interesting display we didn’t notice until we departed Busosanseong two hours after entering was laid into the brickwork in front of the gate. These names and dates represent each of Baekje’s kings from the very beginning of the kingdom in 18 B.C. to its violent demise in 660 A.D. My pictures don’t do it justice, as its actually quite nicely done.

Cartoon map of Busosanseong highlighting key points of interest and the maze of trails (and fortifications) criss-crossing the hill mass. Baekje, Goryeo, and Joseon all built fortifications or other military facilities on this site, each with their own security needs and aesthetic desires in mind.

An interesting compound I didn’t realize was on Busosanseong till we started hiking. The Samchungsa shrine memorializes three Baekje officials whose advice the last king ignored, leading to the tragic destruction of Sabi—and the kingdom—in 660.

The Samchungsa honors two civilian ministers and General Gyebaek who, against his own advice, was ordered to lead 5,000 elite troops east into the narrow mountain passes to face 50,000 soldiers from Silla marching on Sabi. Gyebaek did his duty, falling during the last of four battles he fought against Silla in the Sobaek Mountains. His absence—and that of the kingdom’s finest troops—would be sorely missed when Sabi came under siege.

There are several pavilions located on Busosanseong, none of which actually belongs there. In each case these were relocated from elsewhere by occupying Imperial Japanese troops at the end of the 19th Century. That said, each of the sites that currently hosts a pavilion originally had one of their own, used for the usual dual purpose of rest and relaxation in peace time, and as command posts during war.

The walls of Busosanseong are of the unimproved, packed earth variety, best viewed from the side. These ramparts run for miles on the hill and would have been topped with wooden battlements for further protection and greater defense.

The scenic Baekhwajeong Pavilion, overlooks a sad scene from the 660 A.D. fall of Sabi. It was from the cliffs just beneath this pavilion that the court ladies committed mass suicide by jumping into the river below rather than allow themselves to be taken prisoner. The site remains one of the better known events from Korea’s Three Kingdoms period and continues to conjure up vivid imagery amongst Koreans to this day.

The Geum River (here and in the next pic) lies quite a way below the cliffs. Probably not high enough to kill a jumper, the weight of courtly attire would have nonetheless quickly drowned the aristocratic ladies taking that final leap.

A reminder to us that Busosanseong—like many Korean historical sites—remains an active archaeological site.

The shards of pottery uncovered here continue to yield secrets previously forgotten about how the rulers and people of Baekje lived and, ultimately, died.

Baekje Royal Tombs

While searching for the best access to stretches of the old city walls (Nanseong), we found parking at the Baekje Royal Tombs killed two birds with one stone. This is where many of Baekje’s final kings and their family members remain entombed.

Just beyond the tombs—using the parking lot as a reference point—you stumble upon the foundations of Goranamji, what used to be a fairly impressive temple complex sandwiched between the burial ground and the outer face of Nanseong. The “window” above was, I thought, a lovely way to present a bit of Korean history and architecture long, long gone.

Naseong (Sabi City Wall)

The city walls of Sabi once stretched over 6 kilometers in length, its northern end anchored firmly on the base of Busosanseong. It is considered to have been the first outer city wall ever constructed on the Korean Peninsula. The wall stops at the edge of the Geum River and so does not completely enclose the city. Conventional Baekje military wisdom at the time considered the river itself to be barrier enough, a potentially decisive error given how the entire war came down to the storming of the capital city in 660 . . . by an enemy with a fleet.

Unique amongst the many walls I’ve visited in Korea, this would have been one of the earliest attempts at strengthening packed dirt ramparts with stone, and it displays a certain simple approach to the nonetheless incredible engineering task.

Nanseong runs up and over the hill behind the royal tombs . . . can’t tell you how much I wanted to follow it into the woods!

As well, it continued across the valley until cut by the modern roadway to the east.

On the far side of the road, however, you can see the wall picks up and continues its circuitous path to the river. Would love to have the time someday to walk the entire length!

Gungnamji

Baekje was culturally influenced by several Chinese dynasties, and that influence is visible in the water garden here. More importantly, however, the pavilion set on the island in the central pond is truly beautiful . . . and I now have a model for my future back yard!

A simple reminder here that keeping things as they were in medieval times often requires maintenance to be done much as it was 1400 years ago. These ladies are working hard—up to their waists in pond water—to keep this old site simply gorgeous. Hat’s off, ladies! Job well done.

Jeongnimsaji

One of the oldest Buddhist temple complexes on the Korean Peninsula, not much remains of the original buildings here. What does remain, however, is a 1500 year old stone pagoda of impressive proportions. The foundations of the various sections of the old temple have survived, however, and with a little imagination on the part of the visitor, offer a pretty good idea of how this royal temple—at the heart of the capital—would have looked.

Baekje temples are characterized by the presence of stone pagodas like the one at Jeongnimsaji. Much larger than it looks from a distance, the proportions are actually quite impressive given the period in which it was erected.

The lecture hall of Jeongnimsaji houses a very old stone representation of the Buddha.

A rough depiction, to be sure, but the ring of lotus leaves along the base give away the identity of the figure sitting on the pedestal above. This statue has been dated to the 6th Century, though the head and hat had to be replaced much later after partial destruction resulting from a temple fire.

And this is why I love history so much! Truth can be so much stranger than the most incredible fiction. Here, on the face of the lowest level of the stone pagoda, the victorious Tang army left an inscription, intent to rub the noses of the people of Baekje in their defeat. 1400 years later its virtually impossible to read, but the parts that are legible—in Chinese, of course—sing the self-styled praises of the Tang Dynasty troops and their General, Su Dingfang. Interestingly—and to show how connected the region was even then—Su Dingfang would die in 667, during a defensive campaign against the Tibetans.

GaTabsa Temple

Very quaint little temple complex on the way from the royal tombs heading in toward the main city of Buyeo. Very little information on it though it seems the local area was a center of renewed activity following the conquest of Baekje and virtual abandonment of the capital city of Sabi in 663. Worth stopping by for a quick look if you’re in the area.